How to kill cancer and other rogue cells

November 1, 2010

A protein called perforin punches holes in and kills rogue cells in our bodies, researchers at Monash University and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne and Birkbeck College in London have found. Their discovery of the mechanism of this assassin is published today in the science journal Nature.

A protein called perforin punches holes in and kills rogue cells in our bodies, researchers at Monash University and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne and Birkbeck College in London have found. Their discovery of the mechanism of this assassin is published today in the science journal Nature.

“Perforin is our body’s weapon of cleansing and death,” Monash University Professor James Whisstock said. “It breaks into cells that have been hijacked by viruses or turned into cancer cells and allows toxic enzymes in, to destroy the cell from within. Without it, our immune system can’t destroy these cells. Now we know how it works, we can start to fine tune it to fight cancer, malaria and diabetes.”

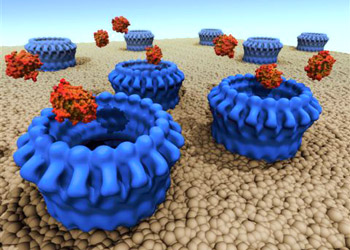

The structure was revealed with the help of the Australian Synchrotron, and with powerful electron microscopes at Birkbeck. Combining the detailed structure of a single perforin molecule with the electron microscopy reconstruction of a ring of perforins forming a hole in a model membrane revealed how this protein assembles to punch holes in cell membranes.

The new research has confirmed that the important parts of the perforin molecule are similar to those in toxins deployed by bacteria such as anthrax, listeria and streptococcus. “The molecular structure has survived for close to two billion years, we think,” Professor Joe Trapani, head of the Cancer Immunology Program at MacCallum Cancer Centre said.

If perforin isn’t working properly, the body can’t fight infected cells. And there is evidence from mouse studies, Trapani said, that defective perforin leads to an upsurge in malignancy, particularly leukaemia.

Perforin is also the culprit when the wrong cells are marked for elimination, either in autoimmune disease conditions, such as early onset diabetes, or in tissue rejection following bone marrow transplantation.

So the researchers are now investigating ways to boost perforin for more effective cancer protection and therapy for acute diseases such as cerebral malaria. And with the help of a $1 million grant from the Wellcome Trust they are working on potential inhibitors to suppress perforin and counter tissue rejection.

Adapted from materials provided by Monash University.