Diagnostic devices the size of a credit card

October 29, 2013

Concept for a microfluidic bioreactor: two chambers separated by a nanoporous silicon membrane (credit: Adam Fenster/University of Rochester)

A silicon nanomembrane developed at the University of Rochester could drastically shrink the power source needed with electroosmotic pumps (EOPs) to move solutions through micro-channels — paving the way for ultra-thin “lab-on-a-chip” diagnostic devices the size of a credit card.

“Until now, electroosmotic pumps have had to operate at a very high voltage — about 10 kilovolts,” said James McGrath, associate professor of biomedical engineering.

“Our device works in the range of one-quarter of a volt, which means it can be integrated into devices and powered with small batteries.”

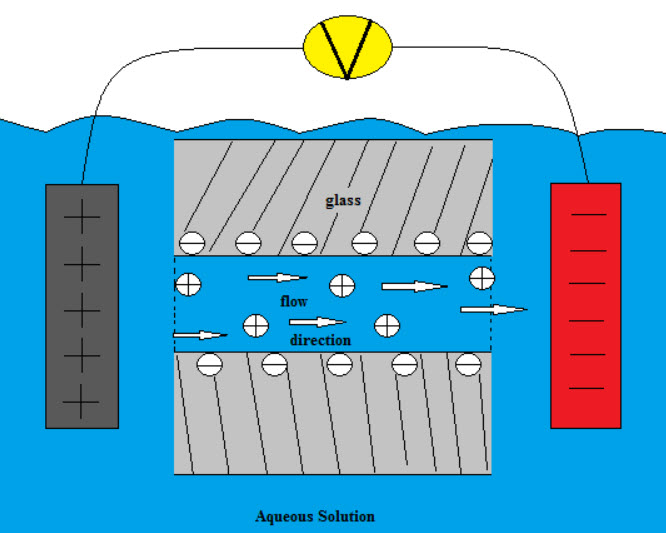

Electroosmotic pumps use a porous membrane between two electrodes to create an electroosmotic flow, which occurs when an electric field interacts with ions on a charged surface, causing fluids to move through channels (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

McGrath and his team use 15-nm-thick porous nanocrystalline silicon (pnc-Si) membranes — 1,000 of these stacked equal the width of a human hair.

The thin pnc-Si membranes allow the electrodes to be placed much closer to each other, creating a much stronger electric field with a much smaller drop in voltage, thus allowing for a smaller power source.

Applications

The nanocrystalline silicon membranes are inexpensive to make and can be easily integrated on silicon or silica-based microfluidic chips, said McGrath.

Besides portable medical diagnostic devices, inexpensive, highly portable devices that process blood samples to detect biological agents such as anthrax are also needed for military and homeland-security efforts.

EOPs could also be used to cool electronic devices, such as laptops and other portable electronic devices.

Abstract of PNAS paper