Are you smarter than a macaw?

June 13, 2016

The macaw has a brain the size of an unshelled walnut, compared to the macaque monkey’s lemon-sized brain. But the macaw has more neurons in its forebrain — the portion of the brain associated with intelligent behavior — than the macaque. (credit: Vanderbilt University)

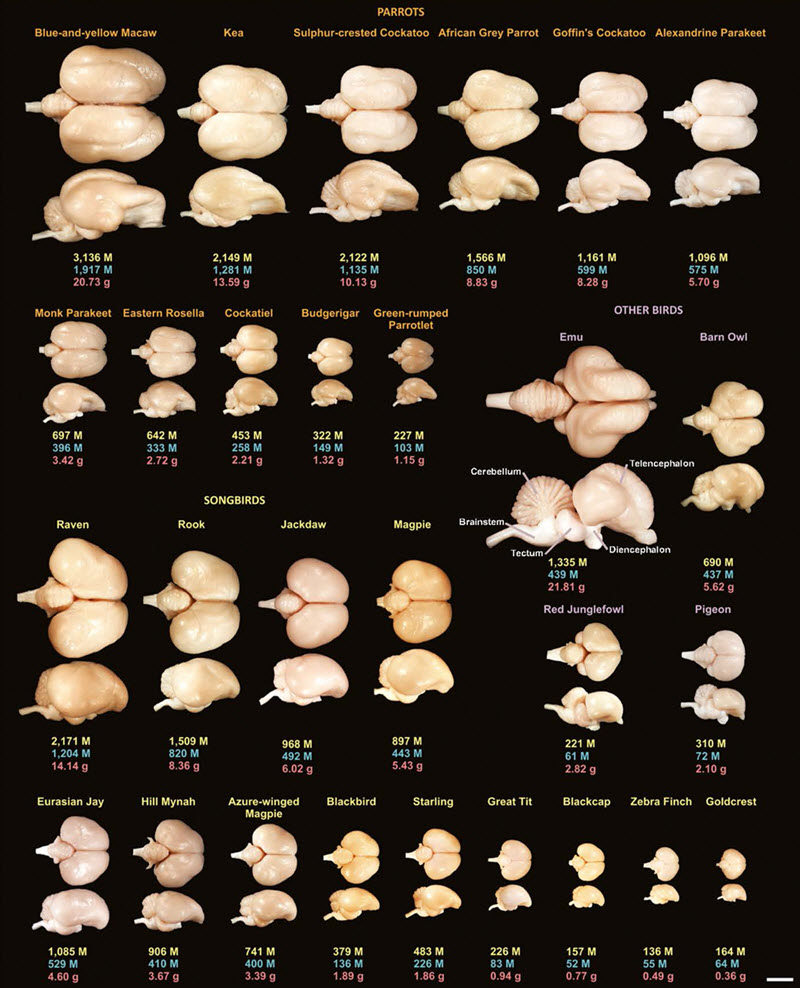

The first study to systematically measure the number of neurons in the brains of more than two dozen species of birds has found that the birds that were studied consistently have more neurons packed into their small brains than those in mammalian or even primate brains of the same mass.

The study results were published online in an open-access paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences early edition on the week of June 13.

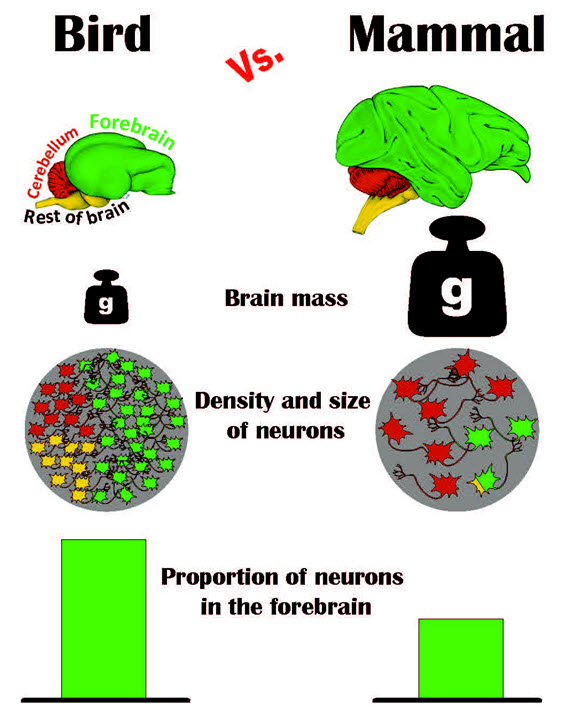

Graphic summary of the results of the avian brain study (credit: Pavel Nemec, Charles University of Prague)

“For a long time having a ‘bird brain’ was considered to be a bad thing. Now it turns out that it should be a compliment,” said Vanderbilt University neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel, senior author of the paper with Pavel Němec at the Charles University in Prague.

The study answers a puzzle that comparative neuroanatomists have been wrestling with for more than a decade: How can birds with their small brains perform complicated cognitive behaviors?

The conundrum was created by a series of studies beginning in the previous decade that directly compared the cognitive abilities of parrots and crows with those of primates. The studies found that the birds could manufacture and use tools, use insight to solve problems, make inferences about cause-effect relationships, recognize themselves in a mirror, and plan for future needs, among other cognitive skills previously considered the exclusive domain of primates.

The collection of avian brains that the scientists analyzed. For each species, the total number of neurons (in millions) in each brain is shown in yellow, the number of neurons (in millions) in the forebrain (pallium) is shown in blue and the brain mass (in grams) is shown in red. The scale bar in the lower right is 10 mm. (credit: Suzana Herculano-Houzel, Vanderbilt University)

So scientists assumed avian brains must be wired differently from primate brains. Two years ago, even this hypothesis was knocked down by a detailed study of pigeon brains, which concluded that they are, in fact, organized along quite similar lines to those of primates.

More neurons in the forebrain than previously thought

Top ten in number of whole-brain neurons and pallium (forebrain) neurons for the avian and mammalian species examined (credit: Seweryn Olkowicz et al./PNAS)

The new study provides a plausible explanation: Birds can perform these complex behaviors because birds’ forebrains contain a lot more neurons than any one had previously thought — as many as in mid-sized primates.

“We found that birds, especially songbirds and parrots, have surprisingly large numbers of neurons in their pallium: the part of the brain that corresponds to the cerebral cortex, which supports higher cognition functions such as planning for the future or finding patterns. That explains why they exhibit levels of cognition at least as complex as primates,” said Herculano-Houzel.

That’s because the neurons in avian brains are much smaller and more densely packed than those in mammalian brains, the study found. Parrot and songbird brains, for example, contain about twice as many neurons as primate brains of the same mass and two to four times as many neurons as equivalent rodent brains.

Also, the proportion of neurons in the forebrain is significantly higher, the study found.

More than one way to build better brains

“In designing brains, nature has two parameters it can play with: the size and number of neurons and the distribution of neurons across different brain centers,” said Herculano-Houzel, “and in birds we find that nature has used both of them.”

Although she acknowledges that the relationship between intelligence and neuron count has not yet been firmly established, Herculano-Houzel and her colleagues argue that having the same or greater forebrain neuron counts than primates with much larger brains can potentially provide the birds with much higher “cognitive power” per pound than mammals.

In other words, there’s more than one way to build better brains. Previously, neuroanatomists thought that as brains grew larger, neurons had to grow bigger as well because they had to connect over longer distances. “But bird brains show that there are other ways to add neurons: Keep most neurons small and locally connected and only allow a small percentage to grow large enough to make the longer connections. This keeps the average size of the neurons down,” she explained.

But that raises troubling questions:

- Does the surprisingly large number of neurons in bird brains comes at a correspondingly large energetic cost?

- Are the small neurons in bird brains a response to selection for small body size due to flight, or possibly the ancestral way of adding neurons to the brain — from which mammals, not birds, may have diverged.

Herculano-Houzel hopes that the results of the study and the questions it raises will stimulate other neuroscientists to begin exploring the mysteries of the avian brain, especially how their behavior compares to that of mammals of similar numbers of neurons or brain size.

Researchers at Charles University in Prague and the University of Vienna were also involved in the study.

Vanderbilt University | Bird Brain: Smarter Than You Think

Vanderbilt University | Study gives new meaning to the term “bird brain”

Abstract of Birds have primate-like numbers of neurons in the forebrain

Some birds achieve primate-like levels of cognition, even though their brains tend to be much smaller in absolute size. This poses a fundamental problem in comparative and computational neuroscience, because small brains are expected to have a lower information-processing capacity. Using the isotropic fractionator to determine numbers of neurons in specific brain regions, here we show that the brains of parrots and songbirds contain on average twice as many neurons as primate brains of the same mass, indicating that avian brains have higher neuron packing densities than mammalian brains. Additionally, corvids and parrots have much higher proportions of brain neurons located in the pallial telencephalon compared with primates or other mammals and birds. Thus, large-brained parrots and corvids have forebrain neuron counts equal to or greater than primates with much larger brains. We suggest that the large numbers of neurons concentrated in high densities in the telencephalon substantially contribute to the neural basis of avian intelligence.