Brain’s frequencies have much to tell scientists

February 8, 2011

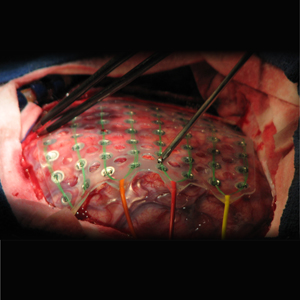

Neuroscientists have closely analyzed where and when the brain becomes active for many years, but now researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are gathering evidence that the frequency of that activity can be a source of important insights. The discoveries are made possible by a grid of electrodes temporarily installed directly on the surface of a patient's brain to help pinpoint the source of medication-resistant seizures.

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have tuned in to precise frequencies of brain activity for new insights into how the brain works.

“Analysis of brain function normally focuses on where brain activity happens and when,” says Eric C. Leuthardt, MD. “What we’ve found is that the wavelength of the activity provides a third major branch of understanding brain physiology.”

The researchers used electrocorticography, a technique for monitoring the brain with a grid of electrodes temporarily implanted directly on the brain’s surface. Clinically, Leuthardt and other neurosurgeons use this approach to identify the source of persistent, medication-resistant seizures in patients and to map those regions for surgical removal. With the patient’s permission, scientists can also use the electrode grid to experimentally monitor a much larger spectrum of brain activity than they can via conventional brainwave monitoring.

Scientists normally measure brainwaves with a process called electroencephalography (EEG), which places electrodes on the scalp. Brainwaves are produced by many neurons firing at the same time; how often that firing occurs determines the activity’s frequency or wavelength, which is measured in hertz, or cycles per second. Neurologists have used EEG to monitor consciousness in patients with traumatic injuries, and in studies of epilepsy and sleep.

In contrast to EEG, electrocorticography records brainwave data directly from the brain’s surface.

“We get better signals and can much more precisely determine where those signals come from, down to about one centimeter,” Leuthardt, assistant professor of neurosurgery, of neurobiology and of biomedical engineering, says. “Also, EEG can only monitor frequencies up to 40 hertz, but with electrocorticography we can monitor activity up to 500 hertz. That really gives us a unique opportunity to study the complete physiology of brain activity.”

Leuthardt and his colleagues have used the grids to watch consciousness fade under surgical anesthesia and return when the anesthesia wears off. They found each frequency gave different information on how different circuits changed with the loss of consciousness, according to Leuthardt.

“Certain networks of brain activity at very slow frequencies did not change at all regardless of how deep under anesthesia the patient was,” Leuthardt says. “Certain relationships between high and low frequencies of brain activity also did not change, and we speculate that may be related to some of the memory circuits.”

Their results also showed a series of changes that occurred in a specific order during loss of consciousness and then repeated in reverse order as consciousness returned. Activity in a frequency region known as the gamma band, which is thought to be a manifestation of neurons sending messages to other nearby neurons, dropped and returned as patients lost and regained consciousness.

The results appeared in December in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In another paper that will publish Feb. 9 in The Journal of Neuroscience, Leuthardt and his colleagues have shown that the wavelength of brain signals in a particular region can be used to determine what function that region is performing at that time. They analyzed brain activity by focusing on data from a single electrode positioned over a number of different regions involved in speech. Researchers could use higher-frequency bands of activity in this brain area to tell whether patients:

- had heard a word or seen a word

- were preparing to say a word they had heard or a word they had seen

- were saying a word they had heard or a word they had seen.

“We’ve historically lumped the frequencies of brain activity that we used in this study into one phenomenon, but our findings show that there is true diversity and non-uniformity to these frequencies,” he says. “We can obtain a much more powerful ability to decode brain activity and cognitive intention by using electrocorticography to analyze these frequencies.”

Adapted from materials provided by Washington University School of Medicine