Diet restriction suspends development in nematode worms, doubles lifespan

June 23, 2014

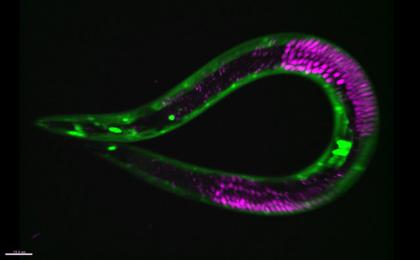

The nematode worm C. elegans with muscle cells fluorescently labeled in green and germ cells fluorescently labeled in red. These cells and others pause at a checkpoint in development and slow their aging when worms encounter a period of starvation. (Credit: Duke University)

Researchers at Duke University have found that taking food away from the C. elegans nematode worm triggers a state of arrested development: while the organism continues to wriggle about, foraging for food, its cells and organs are suspended in an ageless, quiescent state.

When food becomes plentiful again, the worm develops as planned, but can live twice as long as normal.

The results appear June 19 in PLOS Genetics (open access).

The study found that C. elegans could be starved for at least two weeks and still develop normally once feeding resumed. Because the meter isn’t running while the worm is in its arrested state, this starvation essentially doubles the two-week lifespan of the worm.

“It is possible that low-nutrient diets set off the same pathways in us to put our cells in a quiescent state,” said David R. Sherwood, an associate professor of biology at Duke University. “The trick is to find a way to pharmacologically manipulate this process so that we can get the anti-aging benefits without the pain of diet restriction.”

The researchers are now performing a number of genetic studies to see if they can find another way to force C. elegans into these development holding patterns.

“This study has implications not only for aging, but also for cancer,” said Sherwood. “One of the biggest mysteries in cancer is how cancer cells metastasize early and then lie dormant for years before reawakening. My guess is that the pathways in worms that are arresting these cells and waking them up again are going to be the same pathways that are in human cancer metastases.”

Study details

Over the last 80 years, researchers have put a menagerie of model organisms on a diet, and they’ve seen that nutrient deprivation can extend the lifespan of rats, mice, yeast, flies, spiders, fish, monkeys and worms anywhere from 30 percent to 200 percent longer than their free-fed counterparts.

Outside the laboratory and in the real world, organisms like C. elegans can experience bouts of feast or famine that no doubt affect their development and longevity. Sherwood’s colleague Ryan Baugh, an assistant professor of medicine at Duke, showed that hatching C. elegans eggs in a nutrient-free environment shut down their development completely. He asked Sherwood to investigate whether restricting diet to the point of starvation later in life would have the same effect.

Sherwood and his postdoctoral fellow Adam Schindler decided to focus on the last two stages of C. elegans larval development — known as L3 and L4 — when critical tissues and organs like the vulva are still developing. During these stages, the worm vulva develops from a speck of three cells to a slightly larger ball of 22 cells. The researchers found that when they took away food at various times throughout L3 and L4, development paused when the vulva was either at the three-cell stage or the 22-cell stage, but not in between.

When they investigated further, the researchers found that not just the vulva, but all the tissues and cells in the organism seemed to get stuck at two main checkpoints. These checkpoints are like toll booths along the developmental interstate. If the organism has enough nutrients, its development can pass through to the next toll booth. If it doesn’t have enough, it stays at the toll booth until it has built up the nutrients necessary to get it the rest of the way.

“Development isn’t a continuous nonstop process,” said Schindler, who is lead author of the study. “Organisms have to monitor their environment and decide whether or not it is amenable to their development. If it isn’t, they stop, if it is, they go. Those checkpoints seem to exist to allow the animal to make that decision. And the decision has implications, because the resources either go to development or to survival.”

The research was supported by an American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship Award and by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Abstract of PLOS Genetics paper

Organisms in the wild develop with varying food availability. During periods of nutritional scarcity, development may slow or arrest until conditions improve. The ability to modulate developmental programs in response to poor nutritional conditions requires a means of sensing the changing nutritional environment and limiting tissue growth. The mechanisms by which organisms accomplish this adaptation are not well understood. We sought to study this question by examining the effects of nutrient deprivation on Caenorhabditis elegans development during the late larval stages, L3 and L4, a period of extensive tissue growth and morphogenesis. By removing animals from food at different times, we show here that specific checkpoints exist in the early L3 and early L4 stages that systemically arrest the development of diverse tissues and cellular processes. These checkpoints occur once in each larval stage after molting and prior to initiation of the subsequent molting cycle. DAF-2, the insulin/insulin-like growth factor receptor, regulates passage through the L3 and L4 checkpoints in response to nutrition. The FOXO transcription factor DAF-16, a major target of insulin-like signaling, functions cell-nonautonomously in the hypodermis (skin) to arrest developmental upon nutrient removal. The effects of DAF-16 on progression through the L3 and L4 stages are mediated by DAF-9, a cytochrome P450 ortholog involved in the production of C. elegans steroid hormones. Our results identify a novel mode of C. elegans growth in which development progresses from one checkpoint to the next. At each checkpoint, nutritional conditions determine whether animals remain arrested or continue development to the next checkpoint.