Nanotech yarn behaves like super-strong muscle

November 16, 2012

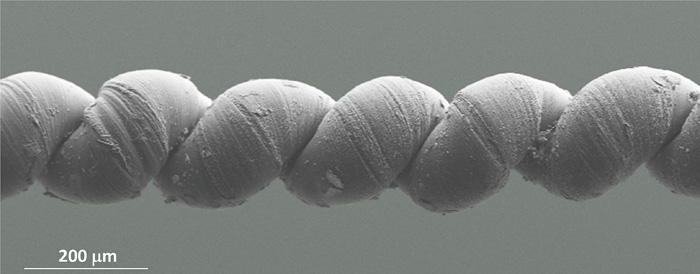

UT Dallas researchers have made artificial muscles from carbon nanotube yarns that have been infiltrated with paraffin wax and twisted until coils form along their length. The diameter of this coiled yarn is about twice the width of a human hair. (Credit: UT Dallas)

New artificial muscles made from nanotech yarns and infused with paraffin wax can lift more than 100,000 times their own weight and generate 85 times more mechanical power than the same size natural muscle, according to scientists at The University of Texas at Dallas and their international team from Australia, China, South Korea, Canada and Brazil.

The artificial muscles are yarns constructed from carbon nanotubes, which are seamless, hollow cylinders made from the same type of graphite layers found in the core of ordinary pencils. Individual nanotubes can be 10,000 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair, yet pound-for-pound, 100 times stronger than steel.

“The artificial muscles that we’ve developed can provide large, ultrafast contractions to lift weights that are 200 times heavier than possible for a natural muscle of the same size,” said Dr. Ray Baughman, team leader, Robert A. Welch Professor of Chemistry and director of the Alan G. MacDiarmid NanoTech Institute at UT Dallas.

“While we are excited about near-term applications possibilities, these artificial muscles are presently unsuitable for directly replacing muscles in the human body.”

The new artificial muscles are made by infiltrating a volume-changing “guest,” such as the paraffin wax used for candles, into twisted yarn made of carbon nanotubes. Heating the wax-filled yarn, either electrically or using a flash of light, causes the wax to expand, the yarn volume to increase, and the yarn length to contract.

The combination of yarn volume increase with yarn length decrease results from the helical structure produced by twisting the yarn. A child’s finger cuff toy, which is designed to trap a person’s fingers in both ends of a helically woven cylinder, has an analogous action. To escape, one must push the fingers together, which contracts the tube’s length and expands its volume and diameter.

“Because of their simplicity and high performance, these yarn muscles could be used for such diverse applications as robots, catheters for minimally invasive surgery, micromotors, mixers for microfluidic circuits, tunable optical systems, microvalves, positioners and even toys,” Baughman said.

Muscle contraction — also called actuation — can be ultrafast, occurring in 25-thousandths of a second. Including times for both actuation and reversal of actuation, the researchers demonstrated a contractile power density of 4.2 kW/kg, which is four times the power-to-weight ratio of common internal combustion engines.

To achieve these results, the guest-filled carbon nanotube muscles were highly twisted to produce coiling, as with the coiling of a rubber band of a rubber-band-powered model airplane.

When free to rotate, a wax-filled yarn untwists as it is heated electrically or by a pulse of light. This rotation reverses when heating is stopped and the yarn cools. Such torsional action of the yarn can rotate an attached paddle to an average speed of 11,500 revolutions per minute for more than 2 million reversible cycles. Pound-per-pound, the generated torque is slightly higher than that obtained for large electric motors, Baughman said.

Self-powered intelligent materials and textiles

Because the yarn muscles can be twisted together and are able to be woven, sewn, braided and knotted, they might eventually be deployed in a variety of self-powered intelligent materials and textiles. For example, changes in environmental temperature or the presence of chemical agents can change guest volume; such actuation could change textile porosity to provide thermal comfort or chemical protection. Such yarn muscles also might be used to regulate a flow valve in response to detected chemicals, or adjust window blind opening in response to ambient temperature.

Even without the addition of a guest material, the co-authors found that introducing coiling to the nanotube yarn increases tenfold the yarn’s thermal expansion coefficient. This thermal expansion coefficient is negative, meaning that the unfilled yarn contracts as it is heated. Heating the yarn in inert atmosphere from room temperature to about 2,500 degrees Celsius provided more than 7 percent contraction when lifting heavy loads, indicating that these muscles can be deployed to temperatures 1,000 C above the melting point of steel, where no other high-work-capacity actuator can survive.

“This greatly amplified thermal expansion for the coiled yarns indicates that they can be used as intelligent materials for temperature regulation between 50 C below zero and 2,500 C,” said Dr. Márcio Lima, a research associate in the NanoTech Institute at UT Dallas who was co-lead author of the Science paper with graduate student Na Li of Nankai University and the NanoTech Institute.

“The remarkable performance of our yarn muscle and our present ability to fabricate kilometer-length yarns suggest the feasibility of early commercialization as small actuators comprising centimeter-scale yarn length,” Baughman said. “The more difficult challenge is in upscaling our single-yarn actuators to large actuators in which hundreds or thousands of individual yarn muscles operate in parallel.”

Additional collaborators are from the University of Wollongong in Australia, Hanyang University in South Korea, Nankai University in China, the University of British Columbia in Canada, the State University of Campinas in Brazil, and Sao Paulo State University in Brazil.

This research was principally funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, with additional funding from the Office of Naval Research, the Robert A. Welch Foundation, the Creative Research Initiative Center for Bio-Artificial Muscle, the Korea-U.S. Air Force Cooperation Program, the Australian Research Council, and the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada.